Learning Module Outputs

Output Types

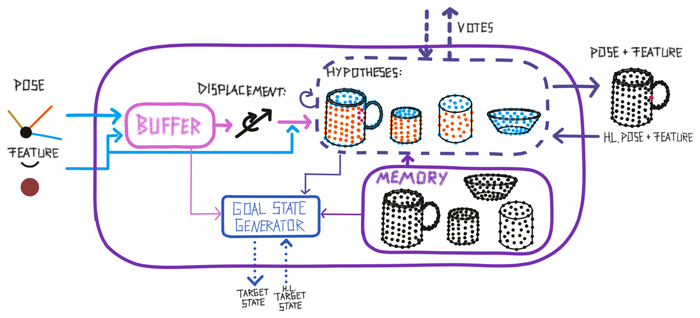

A learning module can have three types of output at every step. All three outputs are instances of the State class and adhere to the Cortical Messaging Protocol.

Pose and Features

The first one is, just like the input, a pose relative to the body and features at that pose. This would for instance be the most likely object ID (represented as a feature) and its most likely pose. This output can be sent as input to another learning module or be read out by the experiment class for determining Monty's Terminal Condition and assessing the model performance.

Vote

The second output is the LMs vote. If the LM received input at the current step it can send out its current hypotheses and the likelihood of them to other LMs that it is connected to. For more details of how this works in the evidence LM, see section Voting with evidence

Goal State

Finally, the LM can also suggest an action in the form of a goal state. This goal state can then either be processed by another learning module and split into subgoals or by the motor system and translated into a motor command in the environment. The goal state follows the CMP and therefore contains a pose relative to the body and features. The LM can for instance suggest a target pose for the sensor it connects to that would help it recognize the object faster or poses that would help it learn new information about an object. A goal state could also refer to an object in the environment that should be manipulated (for example move object x to location y or change the state of object z). To determine a good target pose, the learning module can use its internal models of objects, its current hypotheses, and information in the short-term memory (buffer) of the learning module. The goal state generator is responsible for the selection of the target goal state based on the higher-level goal state it receives and the internal state of the learning module. For more details, see our hypothesis driven policies documentation.

Help Us Make This Page Better

All our docs are open-source. If something is wrong or unclear, submit a PR to fix it!

Updated 6 months ago